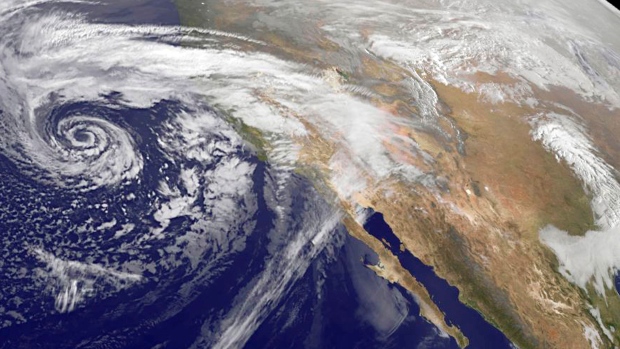

Climate change is a growing concern in British Columbia as drought and wildfires continue to parch much of the province.

It was the hottest June on record for many places around the world, including here in B.C. where at least 64 temperature records were shattered during an intense heat wave.

Climate scientists say we may have to get used to it.

"This is the new normal," said Thomas Pedersen, executive director of the Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions.

Pedersen is part of the government's Climate Leadership Team and will be advising the province on a plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The public is invited to comment on B.C.'s Climate Action Plan until August 17th.

Here are four ways the province is experiencing the impacts of climate change right now.

A close-up view shows the terminus of the Lowell Glacier in Kluane National Park, between B.C. and Alaska in the southwest corner of Yukon, in 2011. A U.S. report on climate change singled out the rapid melt of glaciers in British Columbia and Alaska as a major issue. (Sean Kilpatrick/Canadian Press)

Glaciers are melting

B.C. has 17,000 glaciers and they are all melting, according to Pederson.

He says the implications of melting are profound because it means no late summer water supply, diminished hydro power production, and serious impacts on fisheries and spawning salmon.

"This summer is a good example of what's to come," said Pedersen.

Climate models indicate there will be more precipitation in the winter. However, more of it will fall as rain instead of snow, placing a greater importance on how fresh water is stored and managed.

Fires could burn through the fall

Wildfires started burning early in B.C. this year, and could continue burning longer than usual.

"This year's fire season is likely to go into the fall, from looking at the weather forecast," said fire ecologist Robert Gray.

A 2014 report from B.C.'s Wildfire Management Branch warned the province could face many more fires like the devastating Okanagan Mountain Park forest fire in 2003 seen in here from Peachland. The 2003 fire season was one of the most catastrophic in the history of British Columbia, with over 2,500 fires. ((Richard Lam/Canadian Press))

Gray was part of an inquiry into devastating wildfires that destroyed more than 260,000 hectares of forest and more than 300 homes in Kelowna in 2003.

He says the province could be doing a better job of preventing major wildfires by thinning out forests that have a lot of biomass and debris.

He also says greenhouse gas emissions that are released during forest fires are another major concern.

"We have the initial CO2 emissions during the fire, but then on that blackened landscape we have continued emissions over time."

Growing season is unpredictable

Farmers across B.C. say it has been a growing season full of surprises.

"I just don't know what normal is," said Greg Norton, who owns a cherry orchard near Oliver in the Okanagan and has been growing food for 27 years.

"That's the biggest challenge about climate change. There's no question it's here. The challenge is what do we do? How do we respond within our sector and our regions?"

Norton is a member of the BC Agriculture & Food Climate Action Initiative, developed in 2008 by the BC Agriculture Council to help farmers adapt to the impacts of climate change.

Tom Baumann says farmers in the Fraser Valley are struggling to keep up with the speed at which crops are ripening in this summer's heat. (Jason Williamson/Flickr)

One of the main concerns is water shortages.

Ranchers in the interior are concerned about dugouts drying out and increased drought and wildfires.

In the Fraser Valley, berry farmers are contending with an earlier growing season and increased competition from foreign markets. Norton says he started noticing Chinese cherries in B.C. for the first time last year.

Farmers are also concerned about extreme weather events and high tides crashing over dikes and ruining their soil with salt water.

Scorching temperatures forced the poultry industry to bring in extra ventilation fans for birds this year, and Norton says the heat has caused an explosion of pests.

In Peace River Country, however, he says farmers have had a good two years because of extra rain.

"It's so different for different parts of B.C. So it's hard to have a provincial strategy. It needs to be a regional strategy."

Fish migrating north into more acidic waters

The B.C. coast has seen record warm ocean temperatures of up to three degrees higher than normal, and it is already affecting marine life.

"Fish move with the cool water or they perish," said Rashid Sumalia, a bio economist at the University of British Columbia and author of a recent Vancity report that found sockeye salmon could decline by as much as 21 per cent by 2050.

A new report says climate change will lead to a decline in salmon stock and drive up the price of fish significantly in the coming decades. (Getty Images)

His biggest concern is that fish species migrating north in search of cooler temperatures are heading towards more acidic water.

"One of the scientific findings is that our part of the ocean is a hot spot for ocean acidification," said Sumalia.

He said this is partly due to the dynamics in the Arctic, where fresh water glaciers are melting into the ocean.

"Fish are moving from hot water to cooler waters, and then they're moving to acidic waters."

"This is a double whammy, which is quite scary for many of us looking at this issue."

To encourage thoughtful and respectful conversations, first and last names will appear with each submission to CBC/Radio-Canada's online communities (except in children and youth-oriented communities). Pseudonyms will no longer be permitted.

By submitting a comment, you accept that CBC has the right to reproduce and publish that comment in whole or in part, in any manner CBC chooses. Please note that CBC does not endorse the opinions expressed in comments. Comments on this story are moderated according to our Submission Guidelines. Comments are welcome while open. We reserve the right to close comments at any time.

Note: The CBC does not necessarily endorse any of the views posted. By submitting your comments, you acknowledge that CBC has the right to reproduce, broadcast and publicize those comments or any part thereof in any manner whatsoever. Please note that comments are moderated and published according to our submission guidelines.

Commenting is now closed for this story.